China’s Growth and Challenges to It

Charles Wolf, Jr., RAND Corporation

The Chinese Economic Miracle: Relative and Absolute

Among the four so-called economic miracles of the past half-century – Germany after the Second World War, Japan in the 1970’s and 1980’s, South Korea in the 1970’s through the mid-1990’s, and China between 1980 and 2006 – that of China has, in many respects, been the most remarkable.

Despite occasionally fuzzy statistics and periodic ups-and-downs, China’s average annual economic growth for 1978 through 2006 has been over 9%, compared with the GDP growth record of Japan’s “miracle” of about 6% from the 1960’s through the 1980’s and that of South Korea between the 1980’s and 2005 of about 7% per annum. If China can sustain this impressive record, by 2015 its GDP would be only slightly below that of the United States although its per capita product would be about 25% of that in the United States.

However, there are various possible “fault lines” which could seriously hinder this rosy but plausible scenario. This paper focuses on these challenges for several reasons: one reason is that they have been relatively neglected in much of the public discussion of China’s achievements. Also, it is worth recalling that Japan’s economic accomplishments during the 1980’s were followed in the decade-and-half from 1991 through 2005 by economic stagnation. While remembrance of things past can be instructive, it should be acknowledged that China has numerous opportunities for addressing and overcoming the challenges that it faces and for relieving or mitigating these fault lines. China also possesses greater physical, financial, and human resources for resolving them than we will be elaborating on in this paper.

Eight Major Fault Lines

This paper and the RAND Corporation study on which it is based focus on two core questions:

- what are the major adversities, fault lines or challenges (terms that we hereafter employ synonymously) that might seriously affect China’s ability to sustain its rapid economic growth, and how might these adversities occurs;

- by how much would they affect China’s expected economic growth if they did occur?

The eight major fault lines addressed in this paper were selected through a loose, iterative process involving scholars in China, the U.S. and elsewhere. The fault-lines are illustrative not exhaustive: for example, there are other possible adversities — such as political succession, and demographic challenges — that have not been considered in our analysis. Many of the eight fault lines have been confronted by China in the past two-and-one-half decades and have been managed effectively. Nevertheless, we deliberately focus on how those that have previously occurred might recur in more severe and aggravated circumstances, as well as how others that have not occurred before might arise in the future.

It should be noted that the analysis is conducted on a “one-at-a-time” basis, with the implicit premise that the occurrence of any one of these adversities is independent of the probability and/or severity of others occurring ― an assumption that is not generally warranted. Toward the end of the paper, we will briefly consider some of the interdependencies and potential “clustering” among the adversities. Finally, in arriving at a “bottom line” concerning the likely effects of each of the separate fault lines on China’s expected growth, we use a variety of estimation methods: for example, we employ a standard RAND macro-economic model that views expected growth as a function of the rates of growth in capital formation, employed labor, and in technology and productivity. We also cross-check these base-line calculations along with other methods that have been used by other analysts or that have particular applicability in certain special circumstances, such as WHO’s estimates of “quality-of-life-years” lost by affected workers through the incidence of HIV/AIDS or other epidemic diseases. While the bottom-line estimates of forgone growth are inexact and controversial, in the author’s opinion the estimates are as likely to be on the low (i.e., “conservative”) side as on the high side.

The Fault Lines

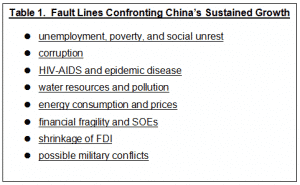

Bearing in mind their illustrative character, Table 1 lists the eight fault-lines:

The order in which the fault lines are listed is not intended to suggest their relative gravity or probability. Two other comments about the list should be noted. The first concerns their heterogeneity: while each one can have serious economic consequences, some such as epidemic disease and possible military conflicts, are not ones usually construed by economists and other analysts as within the domain of economic analysis, despite the fact that they can have serious economic consequences.

Second, it may be helpful to think of the first two fault lines in Table 3 — unemployment and corruption — as institutional and structural in character because they derive from and reflect the incompleteness of social and legal institutions for bridging the gaps between urban and rural areas in the case of rural unemployment and poverty, and the limited scope of the rule of law in the case of corruption. The next three in the Table 1 list — HIV/AIDS and epidemic disease, water resources and pollution, and energy consumption and vulnerability — are sectoral in nature marked by substantial public goods and externality characteristics; while the third group relates to what might be termed financial and capital adversities. Finally, the fourth broad category — security and conflict-related — can appropriately be viewed as constituting a separate group with potentially wide repercussions for most of the others on the list.

I turn next to a brief discussion of each of the fault lines.

Unemployment, poverty and social unrest

China’s total population of 1.3 billion includes a prime-age (18-65 years) labor force of about 750 million. As of 2004, officially registered, urban unemployment was reported as 4-5% of this total. When further allowance is made for rural unemployment for the roughly 100 million permanent migratory part of the labor force, and for disguised rural and urban unemployment, China’s total unemployment rises to nearly 170 million or about 23% of the total labor force.

Furthermore, several factors could result in a worsening of this situation. These factors the population increases that occurred in the 1980’s before the one-child family policy was instituted, the down-sizing of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and the growing effects of China’s efforts to meet its pledges to the World Trade Organization in opening its markets to foreign competition. Such a composite scenario could plausibly be accompanied by increasing income inequality between rural, poorer China and the prosperous coastal areas, perhaps leading to social unrest.

In estimating the bottom line consequences of such a scenario, we assumed there would ensue both a lower rate of growth in employment than China has experienced in recent years, and a redistribution of national savings to provide a social security safety net for the aggravated unemployment and associated rural poverty. The result of this calculation was a modest, and probably underestimated, reduction in anticipated GDP growth of between 0.3-and-0.8% per year.

Economic effects of corruption

Corruption is difficult to define in a way that facilitates measurement. For our present purposes it may be defined as the exercise of arbitrary authority in furtherance of personal interests and in defiance of fiduciary responsibilities to the public interest at large or to duly acknowledged private interests such as those of shareholders of equity corporations.

Corruption impedes economic growth in various ways: by distorting resource allocation in counterproductive ways through such practices as nepotism, bribery, favoritism and contract awards, and by the failure to enforce contracts to protect property rights. Professor Hu Angang of Tsinghua University has estimated that corruption, broadly defined, depletes China’s GDP by as much as 35%. However, this large figure is not directly germane to our concern here because it reflects a diminution in the level of China’s GDP attributed to corruption, rather than the reduction in the rate of growth therein.

To estimate the incremental effect of possible increased corruption we linked two indices: one showing the relative standing of China in a ranking of developing countries with respect to the degree of corruption attributed to them; and a second index that represents an ordering of these countries in relation to their average annual rates of GDP growth. To estimate the incremental effects of a possible worsening of corruption in China, we assume that China’s roughly median standing in the ordering of countries according to corruption might decline to the lowest of the quintile rankings, with the effect of lowering China’s economic growth to that corresponding to the lowered quintile.

The bottom-line reduction in expected growth associated with such a hypothetical worsening of corruption would approximate about 0.5% a year in decreased growth.

HIV/AIDS and Epidemic Disease

According to estimates published by the World Health Organization, HIV/AIDS prevalence in China is between 600,000 and 1.3 million, with an annual rate of growth between 20% and 30%, and a forecasted number of HIV carriers between 11 and 80 million by 2015. Most of this transmission occurs through imperfectly decontaminated blood sold to provincial health-care providers. Adverse effects on economic growth arise from multiple sources including: costs of treatment ranging above $600 per person per year, and between $7 billion and $48 billion annually by 2010; decreases in worker productivity and increases in absenteeism; and in a metric that the World Health Organization refers to as “quality-adjusted years of life.” (QUALY)

The range of scenarios considered in the Fault Lines study and embracing the estimates of HIV/AIDS carriers, costs of therapy, loss of labor productivity and decreases in “QUALY” generates a bottom-line in forecasted reduction of China’s GDP growth between 1.8% and 2.2% per year by 2010.

Water resources and pollution

China’s acute water resource problems are compounded by three elements:

- its annual flow of per capita water resources is less than one-third of the world average;

- China suffers from a sharp maldistribution in availability of the water resources that it has — more than one-third of China’s 1.3 billion population live in the northern part of the country, while less than 10% of its naturally available water supplies are in the northern plain;

- industry discharges and other sources of pollution aggravate the short supply, as well as its maldistribution.

Typically, while major shortages occur in the North China Plain; the South suffers from over-abundance, water run-offs and floods.

In the adverse, although not worst-case, scenarios that were analyzed in the RAND Fault Lines study, the criticality of the water resource problem depended on whether China’s policy-makers engage in less efficient, capital intensive water transfer projects or instead opt for more efficient recycling, and full-cost pricing conservation policies in the North. Recent resource allocations for water transfer projects from South to North suggest that, due to political pressures rather than economic analysis, emphasis is being placed on the economically less-efficient investments in water transfer projects.

According to the standard RAND model used in these bottom-line estimates, this pattern of resource allocation will lower the rate of growth in China’s productive capital stock and reduce aggregate economic growth by between 1.5% and 1.9% per year.

Financial fragility and the state-owned enterprises

Although the market-oriented, private sector has been the principal engine of China’s rapid economic growth over the past two-and-half decades, both the administrations of Presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao have made strong efforts to ensure that the state sector would continue to play a substantial role in and be a substantial part of the Chinese economy. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) in heavy manufacturing, defense, transportation and other infrastructure sectors have been increasingly obliged to conform to market discipline, to reduce costs, and to divest themselves of social overhead and other peripheral activities, while at the same time extending a safety-net to the SOEs through continued if reduced access to the four major state banks for “policy loans” when SOEs’ costs exceeded revenues.

As a consequence, non-performing loans (NPLs) on the balance sheets of the state banks have continued to grow. In 2005, Ernst & Young estimated that NPLs on the balance sheets of the major state banks were between $400 and $900 billion, representing between 30% and 60% of China’s GDP.

In an effort to strengthen the fragile balance sheets of the state banks, the government has replaced some of the NPLs by injections of $40-$50 billion of foreign exchange reserves into the banks’ balance sheets. As a further means of strengthening the fragile financial position of the major banks, the government has embarked on a large-scale effort to privatize three of the four state banks through Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), the largest of which — the Chinese Industrial & Construction Bank — produced $21.9 billion in 2006.

The result has been to reduce the fragility of the banking system. However, the banks remain vulnerable to a possible loss of confidence by depositors and to a massive flight of capital — if, for example, full convertibility of the Renminbi were to be accomplished. In the adverse financial scenarios that we formulated, the result has been to lower savings and investment, to redistribute compensatory financing from capital formation to consumption, and to a bottom-line decrease between 0.5% and 1% a year in estimated annual economic growth.

Possible shrinkage of foreign direct investment

From 1985 through 2005, real foreign direct investment increased by nearly 19% annually, from $2 billion in 1985 to over $60 billion in 2005. Although even at the upper end of this range, FDI has been only about 10% of gross investment in China, its multiplier effects on growth have been substantial. These magnified effects result from the synergistic combination of technology, management, and marketing skills that are typically packaged along with the capital in-flow.

While FDI in China continues to increase (although at a decreasing rate), circumstances might arise in which FDI could shrink. Global capital markets are increasingly integrated. Hence, FDI in China might fall — perhaps deeply and abruptly — if and as the risk-adjusted rates of return on assets accessible to foreign investors in China declined relative to opportunities available or in the process of becoming available in other emerging markets including especially India, East Asia, the Middle East, Russia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America. Thus, shrinkage of FDI into China could occur through a combination of possibly adverse developments within China and improved competitive circumstances in other parts of the world.

For example, unlikely but possible political and social unrest within China, a worsening in the financial fragility of the Chinese banking system, and aggravation of corruption within China’s economic infrastructure, with retrogression in the rule of law and in protection of property rights or an unlikely although possible laggard compliance by China in meeting its WTO pledges, could in combination result in a significant deterioration in China’s attraction for foreign direct investment.

Were such adverse developments to be contemporaneous with corresponding improvements in the investment climate in other emerging market areas, the result could be an appreciable shrinkage of FDI into China. In calculations made in the Fault Lines study, for each reduction of about $10 billion in FDI, the ensuing reduction in GDP growth would range between 0.6% and 1.6% per year in reduced GDP growth.

Possible Military Conflicts

When the Fault Lines study was published in 2003, the most worrisome potential conflict in the Asian region centered on a contingency arising in the Taiwan Strait. Although this remains an abiding concern and will be briefly discussed below, it has been supplanted in immediacy and gravity by the hazardous circumstances emanating from North Korea.

On July 5, 2006, (adroitly timed to coincide with America’s July 4th Independence Day), North Korea conducted seven missile test firings into the Sea of Japan, six of them succeeded in covering their short programmed range, while the seventh ― the longer-range Taepodong missile ― aborted far short of its programmed range. Then, on October 9, 2006, North Korea conducted its “celebratory” nuclear demonstration tests thereby escalating the level of fear and instability in the region. Universal condemnation of the North Korean tests was followed by a U.N. Security Council resolution that applied economic sanctions to the North. In response to pressure ― especially from China ― the North Korean government agreed to resume the stalled six-party talks among China, the United States, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and North Korea.

Under these volatile circumstances, conflict on the Korean Peninsula might arise through any of several precipitating events with consequent impact on China’s growth trajectory. For example, there could be a North Korean invasion of the South based on a real or fancied provocation from South Korea, or a North Korean interpretation of a provocation from the United States as one in which South Korea is closely complicit, or internal conflict within North Korea spilling over into the South, or by “preventive” intervention into North Korea from the South to forestall such a spill-over or to forestall other possible threatening circumstances in the North.

In any of these circumstances, it is plausible that the United States and China would cooperate — either tacitly or overtly — to end the conflict by having their respective military forces intervene to restore and preserve order and especially to prevent further escalation.

In anticipation of the sorts of instability and conflict contingencies referred to above, as well as in response to possible nuclear proliferation in the region occasioned by the North Korean nuclear event, the resulting reallocation of resources in China toward increased military spending and away from capital formation and productivity enhancement can be expected to result in a deceleration of China’s growth.

To shift the focus of potential conflicts to the Taiwan Strait, the current and recent status of relations between the Mainland and Taiwan can be characterized as movement without progress. Both China and Taiwan have been admitted to WTO membership, trade and investment relations between them — mainly conducted through Hong Kong — continue to flourish, and the tone of occasional rhetorical communication between them though rarely warm is not bellicose.

The status quo thus entails benefits for both the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan, as well as for the United States. The benefits of the status quo are especially appealing if compared with some of the possible alternatives to it and the paths that might be associated with movement toward these alternatives. How the present circumstances might nonetheless veer in more belligerent directions or more conflictual directions is discussed in some detail in the Fault Line study and will not be elaborated here. The admittedly crude estimate that is made in that study of the “bottom-line” effects on China’s growth range between 1% – 1.3% reduction, based on the combined effects of a slowing in the rate of civil capital formation by two percentage points due to reallocation of resources within China, and a reduction in the rate of growth in total factor productivity by at least 0.5%.

Summary and conclusions

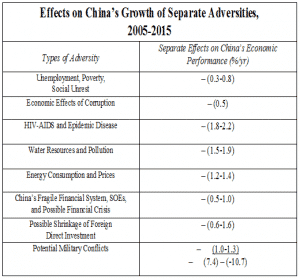

The following table summarizes the aggregate effects on China’s expected economic growth from the eight separate fault lines or adversities previously described.

It’s worth noting that the first five of the specified fault lines are already present in China; in these instances, what we are positing is that they might become worse with the ensuing economic effects shown in Table 2.

Were all of the indicated setbacks to occur, the result would be growth reductions of between 7.4% and 10.7% — thus, improbably registering negative numbers for China’s aggregate economic performance. While the probability that none of these individual adversities will occur is low, the probability that all will ensue is still lower.

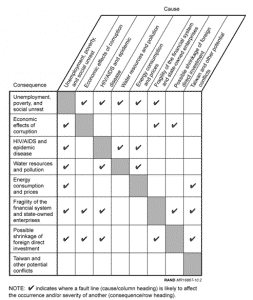

However, the probability that several will occur is higher than their separate joint probabilities would normally imply. The reason is that the separate circumstances are not independent of one another. Several of the separate fault lines may tend to cluster because of these interdependencies. Were the HIV/AIDS or other epidemic diseases to occur in acute form, this would likely increase the probability and/or the severity of FDI retrenchment, and of serious impairment in the functioning of China’s fragile financial system. Similarly, were an internal financial crisis to occur, a likely shrinkage of FDI would be likely to follow. Another clustering might arise in connection with the interdependence among unemployment, poverty, and the incidence of epidemic disease including HIV/AIDS.

Table 3 suggests some of the key interdependencies among the several fault lines.

While some of the specific “bottom-line” estimates of adverse growth effects are subject to question, a few evident conclusions follow from the preceding analysis:

- sustaining China’s high growth rates over the next decade confronts major challenges that require, and indeed are receiving, the focused attention of China’s top political leadership;

- while most of these challenges or fault lines have been adequately managed in the past, some of them could seriously worsen and thereby complicate China’s economic outlook in the future;

- although it is highly unlikely that all of these fault lines will ensue in an aggravated form over the next decade, it is also unlikely that none will do so;

- and finally, the possibility that several of the fault lines will cluster because of the interdependencies among them, is a serious contingency with large potential impacts on China’s GDP growth.