Demystifying College Science Labs

Written by Chandler Ryd

Going into college, most students have prior high school lab experience, and every Hillsdale student spends at least one semester in lab-based physics and chemistry, but neither of those examples gives a comprehensive view of what science majors do on a daily basis. Introductory lab courses tend to be “cookbook” science, where the professor hands out a pre-made procedure and the students follow the steps until they arrive at either a correct or incorrect result.

Sophomore biochemistry major Madison Frame explains it this way: “In a high school lab, you’re given a problem that has a right answer. If you don’t get the right answer, you haven’t done anything special or disproved some basic scientific law—you’ve just done something wrong.”

The reason behind “cookbook” science is straightforward: in order to learn complicated tasks, one must first complete simple ones. For example, when first learning to write an academic essay, the teacher requires a very specific style—for beginners, this typically takes the form of the five paragraph essay—with rigid guidelines for sentence structure and organization. But once the student understands the basic rules of writing academic papers, the teacher gives the student more control over style and content. The same progression applies to labs. When first learning to understand the scientific method, manipulate variables, and use lab equipment, students follow rigid procedures to learn the basics. But beyond the basics lies deeper knowledge and fuller appreciation of the discipline.

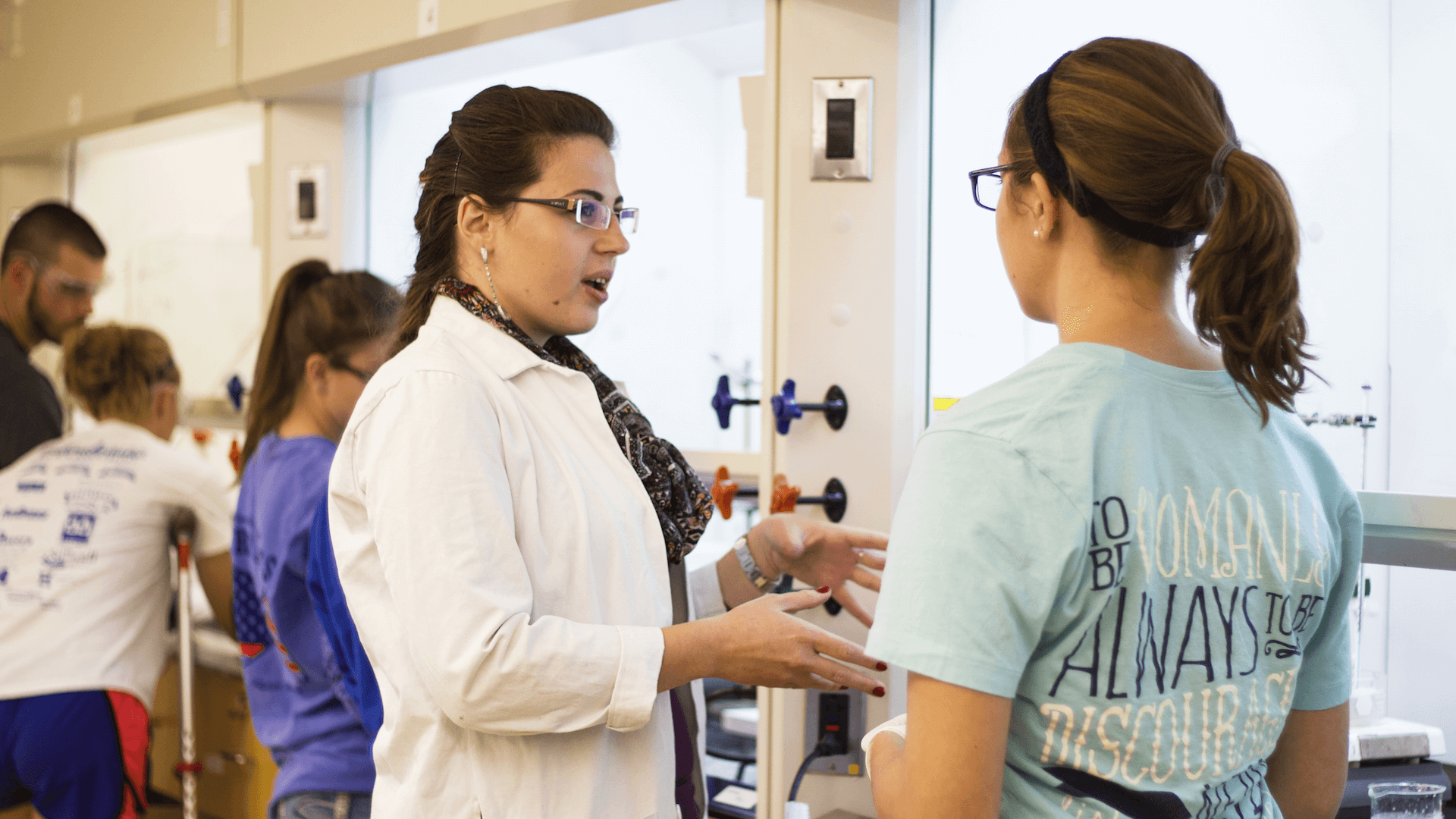

In order to engender students’ lab skills and appreciation, college labs come in two types: classroom labs and research labs. Classroom labs are four-hour affairs that meet once a week and are associated with almost every biology, chemistry, or physics class. The professor assigns a lab exercise, and the students write up their own procedure and prepare their own materials. Students work independently, but the laboratory bustles with sometimes around forty students, TAs, and professors, so help is readily available. After gathering results, students write up a lab report. According to Madison, the time goes by quickly, but labs are exhausting. Hillsdale’s science departments design their classroom labs to mimic real-world laboratories, like what students might encounter in graduate school or in an industrial research facility. “The skills that we teach are skills that students take with them after graduation,” biochemistry professor Dr. Meyet says. “When we write letters of recommendation to higher research institutions, we often use examples of the labs we’ve done with the students.”

Research labs are even more independent than classroom labs. Research labs happen mainly in the summer, when students and professors can devote a full work-day to research for weeks at a time. Students—typically seniors working on thesis research—work closely with their advising professors, who check up on them every few hours to track progress and make adjustments. Research labs require students to approach their work with a genuinely inquisitive and analytical mind. “It’s much more original scientific work, so you’re not necessarily working on a problem that has one right answer. You’re working on a problem few people have worked on before,” Madison says. Research labs also involve much more repetition, sometimes repeating the same procedure dozens of times with small adjustments to collect solid data.

Although most students in research labs are seniors, it is possible to work in one as a rising sophomore. Madison was the only rising sophomore in the chemistry department to work in a research lab over the summer. “I talked to Dr. Meyet, my organic chemistry professor, and asked what I can do to explore different careers, and she said, ‘Why don’t you come and work with me this summer?’ This is what I’ve particularly enjoyed about Hillsdale’s science department.” Hillsdale’s small size allows proactive students like Madison to take advantage of college resources sooner and more often than students at a larger institution.

In both classroom labs and research labs, students learn how to operate real-world instrumentation—all sorts of complicated, gigantic, and hard-to-pronounce tools like infrared spectroscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, and more. “If you go to a big institution, you don’t get that hands-on experience with the instrumentation. Someone else does it for you. This is a big perk of going to Hillsdale. We have a lot of really nice instrumentation that you don’t normally find at smaller colleges. That’s something students can put on their résumé.”

Novelist, filmmaker, and resident root-beer snob, Chandler Ryd, ’18, is the president of the Creative Writing Club. He studies English in his free time. You can usually find him in the periodicals section of the library.

Novelist, filmmaker, and resident root-beer snob, Chandler Ryd, ’18, is the president of the Creative Writing Club. He studies English in his free time. You can usually find him in the periodicals section of the library.