Back to the Basics

The Art and Architecture of Grammar

Written by Nolan Ryan

Gertrude Stein once said, “I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences.” To many people, this may seem an odd thing to say. But in at least one of Hillsdale’s classes, excitement and sentence diagramming come together.

Each semester, the education department offers English Grammar, a three-credit course on the parts of speech, diagramming, and various intricate components of the English language. Drs. Daniel Coupland and Ellen Condict rotate teaching the course, often to a roomful of future teachers, over-eager English majors, and student journalists looking to improve their writing style.

When I took the course as a junior, Dr. Condict opened one of our early class periods by having us recite Lewis Caroll’s “The Jabberwocky” along with her. The first and last stanzas read:

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

At first glance, the words seem meaningless. How on earth is this an actual poem? But upon closer inspection, we find that these nonsense words are filling in as true parts of speech.

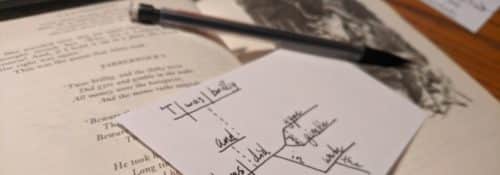

Condict asked us to try identifying what parts of speech these words were. “Toves,” as it turns out, is a plural noun, though none of us knows what exactly a “tove” is. And it follows that if “toves” is a noun, “slithy” must be an adjective modifying that word. Meanwhile, “gyre and gimble” answers the question of what the “mome raths” were doing, so these are verbs.

This exercise proved to us that, even if we aren’t expert grammarians, we all instinctively know how basic kinds of words relate to one another. From here, Condict had us diagramming sentences from the great writers of the West. By the end of the semester, we had diagrammed sentences from St. Augustine, T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, and Ray Bradbury, among many others. We even were assigned the occasional sentence from “Calvin and Hobbes.”

Everyone—not only the youngest schoolchildren—can and should study their own language. The study of grammar gives us a better grasp of how English operates. It also helps us understand on a deeper level the brilliance of a good writer and the meaning of their words.

When considering the importance of grammar, Condict points to a quote from Wendell Berry: “A sentence is both the opportunity and the limit of thought—what we have to think with, and what we have to think in.” Condict says grammar is more than just rules; it is actually like architecture.

“It is the structure that holds language—and therefore ideas—together,” she says. “People tend to think that grammar is mostly to do with apostrophe placement and other punctuation details, but it has everything to do with how we read and think and communicate.”

And nowhere is this architecture of language more apparent than in diagramming sentences. This is an exercise Condict teaches to all of her students, whether on campus or at Hillsdale Academy. “The younger students,” she says, “tend to really enjoy the visual development of a complex diagram.” Meanwhile, most students in her college classroom, she says, are “deeply interested in the diagram we’re producing.”

Condict says grammar is necessary if one wants to become a better stylist. It is impossible to be a good writer without a deep knowledge of grammar. Having a good understanding of grammar keeps us from relying on gimmicks “that will have no staying power.”

Nolan Ryan, ‘20, is an English major and journalism minor from the frigid heart of northern Michigan. If you want to have a long conversation about life and theology, just start by mentioning C.S. Lewis or Emily Dickinson. In the midst of his studies, he occasionally finds time to pursue his love of ’50s music and good coffee.

Nolan Ryan, ‘20, is an English major and journalism minor from the frigid heart of northern Michigan. If you want to have a long conversation about life and theology, just start by mentioning C.S. Lewis or Emily Dickinson. In the midst of his studies, he occasionally finds time to pursue his love of ’50s music and good coffee.

Published in May 2020