A Brief History of Hillsdale, Part 2: The Twentieth Century

Written by Jacky Eubanks

While its origins and Civil War years proved Hillsdale College would not undermine its mission “to furnish all persons who wish, irrespective of nation, color, or sex, a literary and scientific education as comprehensive and thorough as is usually pursued in other colleges in this country,” the twentieth century was to be a new test: the test of freedom from governmental tyranny.

Women’s Rights

If you sift through the archives of the college’s newspaper, dating as far back as the 1880s, the students and faculty of Hillsdale College had been interested in the women’s suffrage movement. Articles range from hailing a 1893 Michigan bill extending full suffrage to women, to recounting suffragette speeches on campus, to celebrating a petition which all the female students of voting age signed in support of the Nineteenth Amendment when it moved to a vote. Students—both male and female—wrote passionate arguments in favor of, and purely satirical arguments against, women’s suffrage.

From 1902 until 1922, Hillsdale alumnus and outspoken women’s suffrage activist Joseph William Mauck served as the College’s president. And nearly a century after the first articles favoring women’s rights were published in The Collegian, famed women’s liberation activists Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes delivered speeches at Hillsdale in 1971 as part of the College’s “Adventures in Ideas” lecture series, in keeping with its commitment to equality regardless of sex.

Civil Rights

Just as the suffrage movement was coming to a fever pitch, the United States entered the First World War. As one might guess, Hillsdale College students served in the armed forces when duty called. Something little-known, however, is that the College refused to comply when the U.S. Army mandated black students be segregated to a separate unit if they wished to participate in the Student Army Training Corp.This happened in 1918, almost fifty years before the Civil Rights Act would end state segregation, and Hillsdale was already—as it had been since its beginning—upholding integration. Thankfully the army turned a blind eye to the practice, and the black and white students trained together in preparation for service overseas.

A major event that rocked the nation almost forty years later was Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, causing her arrest and igniting the Civil Rights movement. That same year, Hillsdale College’s football team went undefeated. What is the correlation? When the team was invited that year to play at the Tangerine Bowl stadium in Orlando, Florida, they were told they had to leave all the black players behind because Southern bowl games wouldn’t allow them to play. In keeping with their values, the entire team declined the offer to play at a major stadium if they could not take the whole team. “Everybody went or nobody went,” player David Trippett, ’58, said in an interview.

Nate Clark, ’57, one of the black players, recalled in an interview, “I felt bad for the team because it deprived them of the opportunity to play in the bowl, but I was proud of the guys who made the decision because we couldn’t go as a team.”

The team’s unanimity in refusing the offer on principle was a shining example of the students’ and school’s commitment to equality. In reference to Rosa Parks, it should be noted that the famed Civil Rights leader decades later, in 1999, chose Hillsdale College to be the sight of her summer camp program “Pathways to Freedom,” which toured the historic Underground Railroad sites around the College and held lectures in the Dow Center. (One such site is rumored to be the College’s student residence Dow House, which appears to have a sealed-off tunnel that leads to the Sigma Chi fraternity house a few yards down the street. Another notable site is the Munro House, a bed-and-breakfast in nearby Jonesville.)

Freedom from Tyranny

This legacy came under fire when the Education Amendment of 1972 was passed. You’ll know it for its Title IX. Although likely created with good intentions, it had far-reaching consequences: any educational institution that received any kind of federal money, even in the form of student loans or Pell grants, became subject to government mandates. Simply because some Hillsdale students received federal aid, the College itself was subject to rules and regulations regarding everything from hiring practices to reporting the percentages of minority students enrolled.

This was problematic for several reasons but most especially because it interfered with the College’s “race-blind” practice in admissions and hiring. The College had never kept track of how many students belonged to which race, as this would have clashed with its founding principles of providing education “irrespective of nation, color, or sex.” To live up to that mission, to be truly “irrespective,” means the very factors the government wants reported must be completely excluded from the admission or hiring process, making any acceptance based on merit alone. If the College were to abide by the government’s statutes, it would necessarily compromise its founding principles.

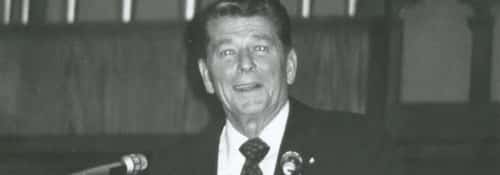

After battling it out in the courts for twelve years, the College came to the decision that it could not, and would not, accept even federal loans or grants, and instead turned to the private sector for financial support in order to maintain its integrity. This direction took Hillsdale College to the forefront of conservative education, especially in lieu of the Conservative Resurgence of the ’80s. Its bold move to, “with the help of God, resist, by all legal means, any encroachments on its independence” attracted the likes of Ronald Reagan, bringing the president to campus as a guest speaker. Once again, by simply acting according to its founding principles, the small Midwest college stood up to state tyranny and proved itself to be a beacon of freedom and equality.

Is Hillsdale College perfect? Of course not. But as Ronald Reagan said in his speech “A Time for Choosing,” “If we lose freedom here, there is no place to escape to. This is the last stand on earth.” If Hillsdale and colleges like us succumb to the ever-growing force of government statutes, mandates, and regulations, we inevitably relinquish the very thing our forefathers fought and died for in the American Revolution, the Civil War, World War II, Korea, Vietnam; the very thing for which millions of immigrants fled to the U.S. from Cuba, the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany; the number one thing Americans pride themselves on: freedom. In the struggle to create and maintain freedom, Hillsdale College has since its founding played a small but necessary role.

For further reading on Hillsdale College in the twentieth century, see Arlan K. Gilbert’s The Permanent Things: Hillsdale College 1900–1994. Hillsdale, Mich.: Hillsdale College Press (1998).

Jacquelyn Eubanks, ’20 is an award-winning author with a passion for books, tea, and mountains. Someday she’ll be a world traveler, but for now you can find her typing away at her newest novel.

Jacquelyn Eubanks, ’20 is an award-winning author with a passion for books, tea, and mountains. Someday she’ll be a world traveler, but for now you can find her typing away at her newest novel.

Published in April 2019