Gash Gold Vermillion: Poetry Recitations and Art

Written by Kate Cavanaugh

Lawson Doden walked into his professor’s office, holding an orange in his right hand and a poem in his left. His English professor had asked him to recite and analyze a portion of John Milton’s work. He set the poem face down on his desk and cleared his throat.

“Of Man’s First Disobedience, and the Fruit / Of that Forbidden Tree…” He began, gesturing violently with his orange. His professor squinted at the lines of the poem, closely following every word he said.

“…That to the highth of this great Argument / I may assert th’ Eternal Providence, / And justify the ways of God to men.” Lawson set his fruit down on his desk triumphantly and walked out of his office without another word.

Students have many different ways of dealing with the anxiety of recitations. Some recite whole poems with their eyes closed. Others pace around the small office wildly. Lawson had a partiality for fruit and dramatic effect.

Poetry recitations can be mildly terrifying. But, I promise you, they are not all bad. Recitations actually taught me to love poetry. I honestly didn’t feel comfortable with poetry until I was forced to memorize it. Recitation immerses you into a poem, forcing you to not just glaze over it but to know it. You feel the cadence of each line as you practice, and you begin to notice why the poet chose one word over another. After you give your recitation, you carry the poem with you. Your memorization of one poem fuels your encounter with others.

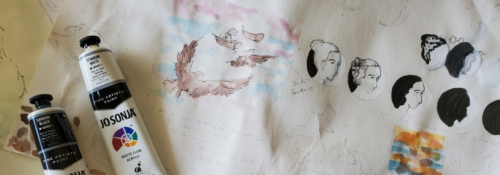

For me, poetry fueled my art. I found little bits of poetry popping into my head as I did my thumbnail sketches for my next project. The prompt was “metamorphosis”: we were to draw one thing transforming into another. Taking the newsprint paper we use for drawing thumbnail sketches, I began a few haphazard sketches. I drew a woman’s face and let it fade into a crescent moon and heard the Lady of Shalott cry out, “I’m half sick of shadows!” I sketched an eagle and then realized it was “pursuing the horizon,” like the man in Stephen Crane’s poem, who sped round and round, except this bird’s pursuit was not futile: it rested on the waves, its feathers rose up into canvas, and it sailed on.

Poetry is not a collection of cheesy, inspirational couplets or a blurry set of vague words. It is alive. Poetry wrestles with realities we live with: death, the quick passage of time. The first poem I ever memorized, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 60, dealt with such realities.

“Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shores,” Shakespeare writes, meditating on human mortality, “So do our minutes hasten to their end.” Poetry contends with the facets of existence that we do not want to face, but it does so softly, with elegant language and gentle rhythm. However, poetry isn’t only about suffering; it is about our response to suffering. Shakespeare ends this sonnet: “And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand / praising thy worth despite his cruel hand.” In light of human mortality, Shakespeare unveils beauty and offers hope through poetry.

The ending of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s poem, “The Windhover” is another piece of a poem that lingers in my mind. In this poem, Hopkins writes about the relationship between suffering, beauty, and love. He describes land that “Shines” when it is plowed, showing how beauty unfolds out of the broken soil. He ends the poem by writing about hot coals breaking open and catching fire: the “blue-bleak embers… / Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold vermillion.” In the breaking open of the embers, there is a brilliant gold-red, just as in the breaking of the land, there is a certain shine. Hopkins shows the reader how vivid color and richness and beauty all spring out of brokenness. Like Shakespeare, Hopkins’s response to suffering to find hope by enshrining beauty.

Both Shakespeare and Hopkins seek to preserve beauty. That is also the work of an artist. For Hopkins, that beauty breaks forth from struggle. For an artist, it comes only after a struggle with a blank sheet of paper and a plethora of haphazard ideas. Poets and artists ultimately come together in their mutual search for beauty as the paintbrush of an artist, dipped in red-gold, streaks across the page, “gashing gold-vermillion.”

Like the artist and the poet, the student too has a duty, and a need, to preserve beauty. By memorizing every last preposition to recite a poem, by clinging to bits of poems read in class, and by allowing different lines to flower in his or her mind, the student, like the artist and the poet, enshrines beauty.

Professors Share: Poetry Appreciation Month

Let It Go: How an Art Elective Taught a Senior to See the World Differently

Read More about Hillsdale Art Majors

Kate Cavanaugh, ’23, is an English major who flirts with graphic design in her spare time. Besides writing for the blog, she can be found mastering the creation of faux london fogs at saga. She can also be glimpsed power-walking to her one o’clock, as the making of faux london fogs can be time consuming.

Kate Cavanaugh, ’23, is an English major who flirts with graphic design in her spare time. Besides writing for the blog, she can be found mastering the creation of faux london fogs at saga. She can also be glimpsed power-walking to her one o’clock, as the making of faux london fogs can be time consuming.

Published in June 2021